History: Indigenous Peoples

The Pantanal has been home to a variety of different indigenous peoples. Indians encountered by early settlers were resourceful and adaptable to this semi-aquatic environment. They included the Paiaguá "Canoe Indians", the Terena who were accomplished farmers, and the fierce horse-riding Guaicurú - described by some as the "Apache of South America".

Records from the early Portuguese and Spanish expeditions beginning in the 1540s provide some insights into indigenous cultures at that time. These early expeditions coincided with the conquest of Peru, and were aimed to open up new territories - while also searching for gold and the rumored city of El Dorado.These included expeditions by Aleixo Garcia (1521) and Álvar Núñez Cabeza da Vaca (1540). Jesuit colonies were also established by the Spanish nearby in modern-day Paraguay and Bolivia - along with a small settlement in the Pantanal called Xeres near the modern town of Miranda, founded in 1579. However, this was destroyed in raids by the Guaicurú and other indian tribes. Further mission settlements were attempted, but these were also destroyed - this time by Portuguese expeditions of Bandeirantes such as Antônio Raposo Tavares in the decades 1630 and 1640.

Among first tribes to be reported were the Xaray, who were adapted to the environment, and inhabited the lower flood-prone Pantanal regions. Their name became associated with a mythical inland ocean (the Sea of Xararés) which is what the Europeans originally thought the Pantanal to be. Other tribes were also present - mostly speaking a common language, Guaraní.

Within two centuries, the old tribal names disappeared - as indigenous peoples were impacted by disease, such as smallpox and influenza, and by the inward push of European colonists, miners, and slavers. Over the years, several large-scale bandeirante expeditions passed through the region. These expeditions travelled on foot from São Paulo and other Portuguese settlements to find gold and gather indian slaves (which were even more lucrative), sometimes taking years to return. They were responsible for annihilation of many indian tribes - although the great distances involved, and aquatic landscape of the Pantanal helped limit their impact here. Nonetheless, the fact that Portuguese colonists took the lead exploiting the region (despite it being Spanish territory at the time) is a key reason why modern-day Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul eventually became part of Brazil.

Bandeirantes return with slaves, by Jean-Baptiste Debret.

The discovery of gold in Cuiabá by Pascoal Moreira Cabral in 1719 increased the number of Europeans entering into the region. This triggered even more conflicts. The dominant tribal groups in the Pantanal region at this time were the Paiaguá, the Guaicurú, and the Bororó.

The Paiaguá

The Paiaguá were one of several "canoe indian" tribes and perfectly adapted to the Pantanal. They believed themselves to be spiritual descendants of the Pacu (a notable fish in the region). They were also strong swimmers and canoe builders. They were viewed by Europeans as a considerable threat - frequently attacking flotillas moving along the Paraguay River. In his book, Red Gold, the historian John Hemming notes that large shipments of gold (originating from goldfields in Mato Grosso) were sometimes lost or sunk in these attacks. The Paiaguá reportedly fought by jumping into the water, and hiding below their upside-down canoes. They'd then sneak up on their adversaries, using their canoe hull as a useful shield in the event they were discovered. Once in range, they'd suddenly right their boats - firing several volleys of arrows in the time that it took the Europeans to fire one.

Eventually the threat was countered by large-scale Portuguese expeditions (in 1730 and 1734) to punish the Paiaguás and prevent further attacks. The Paiaguás were scattered and largely reduced as a result. The bulk of those remaining fled into Paraguay - living on the streets in the capital, Asunción. Their eventual fate was conscription into the army of Francisco Solano López during the Paraguayan War. Although the Paiaguás are now considered extinct, another of the "canoe indian" tribes, the Guató still exists in small numbers.

The Bororó

The Bororó, who were originally located near Cuiabá, north of the Pantanal, were the tribe most impacted by the discovery of gold in 1719. This discovery occurred in their lands - bringing them into conflict, and causing a many deaths from introduced diseases. Most of the Bororó territory was lost, with the remaining population fragmenting into different groups. These groups continued to suffer at the hands of Europeans, despite their best efforts to retreat and minimise further contact with the advancing colonists.

One of these fragmented groups, the Eastern Bororó (also known as the Coroados, or crowned indians) became the protagonists of the fiercest resistance in the region through the 19th century when a road was pushed through the middle of their remaining lands. This led to 50 years of constant warfare - which ended with their peaceful pacification in 1887 by the renowned explorer and founder of Brazil's Indian Protection Service, Cândido Rondon.

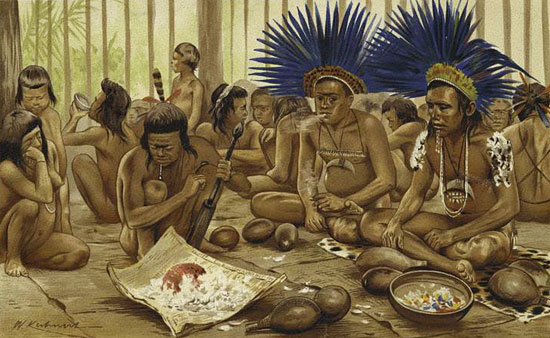

Today, the Bororó are spread across a discontiguous set of demarcated lands which have continued to decrease in size as a result of encroachment by farmers and settlers. The population now numbers about 1,600 people.

Funeral feast of Bororó Indians, Central Brazil, by Wilhelm Kuhnert.

Guaicurú

The Guaicurú are another significant tribe, notable as one of few South American tribes to transition to the use of horses in warfare. For this reason, they're often referred to as the Indios Cavaleiros (Rider Indians), but have also been referred to as the Apache of South America.

Wild horses were plentiful in the Pantanal and nearby Chaco - originating from horses which escaped or were lost from early Spanish expeditions into Paraguay, Bolivia and Argentina in the 1540s. These horses proliferated, with wild herds soon reaching several thousand animals. The Guaicurú indians learned animal management techniques, and adopted the horse in a similar fashion to the Plains Indians of North America.

Guaicurú warriors on horseback, by Jean-Baptiste Debret.

The Guaicurú were nomadic - and mastery of horses made it easy for them to spread their domination throughout the Pantanal and nearby Chaco. Through the 17th and 18th Centuries, the Guaicurú allied themselves with the Paiaguá, and constituted a significant threat to the aspirations of both the Portuguese and Spanish in area. The Paiaguá and Guaicurú's combined forces and complimentary skills meant that indigenous populations could effectively deal with almost any European force coming into the region by land or river. In battle, the Guaicurú typically formed guerrilla bands, setting ambushes and leading lightening raids to hit their adversaries when they least expected it. The Guaicurú reputedly charged into battle naked but for jaguar skins, clubs, lances and machetes; crouched low on their horses or riding on the horses' sides to avoid being an easy target. They didn't use saddles or stirrups, and had just two chords for reins.

However, with the demise of the Paiaguás at the hands of larger and better-armed Portuguese expeditions, the Guaicurú later allied themselves with the Guaná (or Terena), who were an agricultural people. The combination of fast horse-mounted warriors backed by a large stable agricultural society offered advantages to both peoples. Besides skirmishes with Europeans, this alliance also became dominant over other local tribes. However, "captives" and subject tribes were generally treated with kindness and not humiliation - with them simply paying a tribute, or being employed in domestic or non-agricultural activities.

The Guaicurú had been among the first tribes in the region to encounter Spanish colonists, and had been targeted by numerous Spanish military expeditions from Asunción fearing that the Guaicurú would invade and overrun the town. As one contemporary noted, neither the Guaicurú nor the Spanish recognised limits to their territories and it was inevitable that the two cultures would run into conflict. When the Spanish were unable to win militarily, they resorted to treachery. In 1677, the Spanish Commander-in-Chief, General José de Avalos, let it be known that he wished to marry one of the Guaicurú chiefs' daughters - appearing before them in traditional Guaicurú dress to impress them. A wedding date was fixed for 20 January 1678, with all the Guaicurú chiefs and their families being invited to the festivities in Asunción, plied with food, drink and accommodated in the finest houses. In the meantime, Spanish soldiers snuck back to the Guaicurú villages and prepared to mount a major attack. These soldiers were spotted by scouts, and the Spanish attack failed. However, back in Asunción, more Spanish soldiers set upon the Guaicurú chiefs and their families - massacring around 300. This event long remained in the Guaicurú memory - making them implacable enemies of the Spanish and Paraguayan for centuries to come.

Although the Guaicurú posed a potential threat to the Portuguese, the Portuguese Crown recognised their strategic value. The Guaicurú's strength proved one go the most effective means for countering Spanish (and later Paraguayan) ambitions in the region. Improved relations between the Portuguese and the Guaicurú/Guará alliance were formalized in 1791 with the signing of a peace treaty. This granted the Portuguese the right to maintain their settlements - and the ensuing peace saw growth in the recently established fortifications and towns such as Fort Coimbra (1775), Corumbá (1778), and Miranda (1778).

Peaceful relations with the Guaicurú allowed the Portuguese to consolidate their influence in the Pantanal, at the expense of their Spanish-speaking neighbours. The Pantanal had originally been Spanish territory but the presence of Portuguese settlements and fortifications made this mute, and led to the Treaty of Madrid (1750) in which the Portuguese territories were considerably expanded. Even so, the territory of Mato Grosso was still the subject of dispute. This finally boiled over in 1864 when Paraguay sought to forcibly annex the territory through what later became known as the War of Triple Alliance. Brazil's relations with the Guaicurú paid off - with the Guaicurú providing vital support to the Brazilian side, directly engaging and disrupting Paraguayan forces.

As a reward for their assistance in the war, the Brazilian Empire formally recognised Guaicurú land. They were allocated a block of land in the Serra do Bodaquena which is still held by their descendants, the Kadiweú, today. Sadly, the tribe now only numbers about 1500 people.

The Terena

The Terena are the last survivors of the Guaná nation and are, today, the most numerous indigenous group within the Pantanal region, having a population of around 13,000. The Terena had their roots in the Chaco region bordering between Brazil and Paraguay. However, with pressures from growing Spanish settlements, and conflicts with other tribes, the Terena moved deeper into Brazil and the Pantanal. It was during this period that they joined forces with the Guaicurú, who helped protect them from competing tribes and the Portuguese.

Sadly, historic animosities with the Paraguayans meant that they were victimized by the invading Paraguayan troops - with their villages and crops looted or destroyed. Worse still, many of their lands were later appropriated by Brazilian officers and merchants profiteering in the aftermath of the war.

Of all the tribes in the region, the Terena were the most receptive towards the establishment of good relations with the Portuguese. They had a strong agricultural tradition - being tillers of the soil, cultivating corn, sweet cassava and manioc, sugarcane, cotton, tobacco, and other plants. They also manufactured simple goods such as cloth, hammocks and sashes - which they then sold in Brazilian markets. Their understanding of farming and trade enabled them to better integrate into Brazilian society compared to other tribes. This made them valuable employees - but also often made them the target for exploitation from unscrupulous cattle ranchers and land cheats.

Multimedia Links

Image credits: Print of Guaicurú chief leaving to travel, by Jean-Baptiste Debret.

Photos: Bandeirante, Sunset, and Kingfisher (Andrew Mercer)

Pantanal Escapes