History: Paraguayan War

This war, also known as the War of Triple Alliance, arose out of Paraguay's troubled relationship with its two giant neighbours: the Empire of Brazil, and Argentina (then still a loose confederation of states). The area between these heavyweights - known variously as Banda Oriental, Cisplatina, and eventually as Uruguay - was hotly contested, with the major powers all vying for influence.

Uruguay's strategic location meant control of the Rio de la Plata (River Plate), and ocean access for river transport networks reaching into Paraguay and inland Brazil. At that time, any goods being transported into or out of Paraguay, and the western inland regions of Brazil, needed to pass through the port of Buenos Aires - where the Argentines were free to inspect, block, and charge duties as they saw fit. The region was doubly important for Brazil due its influence on the southern-most Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul which had, itself, been fighting for independence.

Things came to a head in November 1864. Angered by Brazilian actions against the faction which he backed in Uruguay, López seized the Brazilian passenger steamship, Marquês de Olinda, soon after it left the Paraguayan capital, Asunción, on its monthly scheduled service to Mato Grosso. Note that the Mato Grosso territory combined the areas now covered by the Brazilian states of Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul (the later was split out as a separate state in 1977)

Onboard the Marquês de Olinda was the recently appointed Governor of Mato Grosso … along with the army garrison payroll. The captured steamship was pressed into service with the Paraguayan Navy, and the captured gold was used to help buy new armaments from Europe. The governor, and the ship's passengers and crew, were thrown into prison where they later died of torture and starvation. López closed the waterways - ensuring that news of the event didn't reach the outside world until several weeks afterwards.

In the weeks that followed, López sent cavalry to harass and capture Brazilian farms and settlements within disputed territory across the Apa river. He also sent a detachment of soldiers, led by his brother-in-law, by steamship to the Brazilian river port at Corumbá. Once there, they disembarked and took over the town - looting and pillaging, and sending the spoils back downriver to López in Asunción. From here, the Paraguayan forces fanned out to capture most of the area now covered by the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso do Sul. The strategic location of Fort Coimbra was also captured in a battle which pitted 4,000 Paraguayan troops against the small contingent of 157 Brazilians led by Lieutenant-Colonel Porto Carreiro. After two days of bombardment, and out of ammunition, the Brazilians abandoned the fort and retreated to Cuiabá aboard the gunboat Anhambaí, where they broke the news of the invasion to the acting Governor of the territory.

The Paraguayans' actions were opportunistic, or possibly diversionary. Rather than moving their forces northwards onto Cuiabá, López sent the bulk of the his forces south towards the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul and into Uruguay - with his primary objective being the control of the Rio de la Plata waterway.

The Brazilians were ill-prepared, and the remoteness of the Mato Grosso territory worked in the Paraguayans' favour. Refugees and survivors faced an overland journey of a month or more before reaching Rio de Janeiro to inform Brazilian Emperor, Dom Pedro II, with news of the invasion. Raising volunteers and materials, then marching them back overland (about 2,000 km) also took time. As such, it was a year later - in December 1865 - before the first Brazilian force of about 2,800 men arrived back on the scene. The territory's size and difficult terrain meant that the recapture of Mato Grosso was a slow campaign which was more notable for long marches and disease than for actual fighting. Corumbá was freed in June 1867, with the remainder of the territory fully recaptured in April 1868. The Paraguayans looted everything they could - destroying whatever couldn't be carried off. As a result, the region's farms and towns, such as Corumbá were abandoned and in ruins - requiring almost total post-war reconstruction.

Brazilian officers involved in the Paraguayan War.

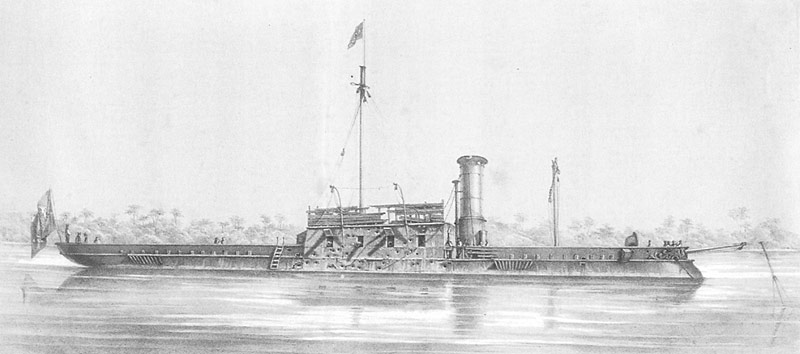

López's campaigns ran into much bigger problems in the south. These territories were less remote, and there was far greater resistance. Furthermore, the route into Rio Grande do Sul required López to cross into the Argentine province of Corrientes. This effectively meant López declaring war on three countries simultaneously: Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay. These three countries were normally rivals, but the arrival of a common threat led them to combine their forces and respond to the Paraguayan invasion. Hence, the "Triple Alliance" was born. The southern campaigns involved several large land battles - along with naval engagements using ironclad river gunboats along the Paraguay River.

Heavy damaged ironclad, Brasil, limps home after engagement at Curuzo Fort in 1866

The Paraguayan War became the bloodiest in South American history, having casualty figures comparable to the American Civil War. Despite their lack of preparation at the start, Brazil and Argentina had much greater resources. They were able to raise larger armies, purchasing the latest weapons from Europe and North America - turning the tables on López and taking the battles back into Paraguay. López steadily refused peace offers, stating that the only options were Victory or Death. Sadly, it was death - and a lot of it.

Francisco Solano López remains a divisive character. For most of the world, he was a cruel and self-obsessed tyrant - responsible for the utter destruction of his country, and the death of most of its population. It's widely reported that 60% of Paraguay's general population died either as a direct result of the war, or through starvation and linked epidemics. Up to 90% of the male population was lost - creating a significant gender imbalance for decades to come. The Paraguayans fought extremely bravely - fanatically according to others - preferring to fight to the death or sacrifice their lives rather than surrender.

This meant a long and very tough campaign for the allied forces of Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay when they crossed over into Paraguayan territory. However, the Paraguayan view is that López was a national hero who demonstrated the strength of his convictions by refusing to be taken alive. After the allies took the Paraguayan capital of Asunción in 1869, López was forced to wander the countryside, fighting a guerrilla campaign for over a year with an ever decreasing army - before finally being cornered in the valley of Cerro Corá (now a Paraguayan National Park, located about 60 km south of the Mato Grosso do Sul town of Bela Vista).

López's mistress, the Irish courtesan Eliza Lynch, is another interesting character in this story. Within Paraguay she's seen as a national heroine, and as a forerunner to Argentina's Evita Peron. However, other accounts by historians and contemporaries depict her as the power behind the throne, and influencing López's judgement.

Battle of Acosta-Ñu, by Pedro Américo.

The ugliness of the war, and desperation of the Paraguayan cause near its end is illustrated by the Battle of Acosta-Ñu. With most of the able-bodied male population already slaughtered, López and his generals resorted to using children and old men to bolster their numbers. This battle took place near the cental Paraguayan town of Eusebio Ayala. López and the bulk of his forces had fled on steamships along the Yhaguy river (a small tributary of the Paraguay). When the boats became bogged down in marshlands, they were abandoned and torched at a place now known as Vapor Cué (Place of steam). López continued overland, attempting to shield his retreat by deploying his remaining force of 6,000 against the pursuing allies. The allies numbered about 20,000, and were fresher and better armed. By contrast, López's forces were exhausted, with lack of weapons and ammunition. Many of the Paraguayan soldiers were children between the ages of 9 and 15 years - with some reportedly as young as 6 years. Some wore fake beards or painted moustaches to hide their age. The Paraguayans' refusal to surrender meant that a battle ensued. The allied forces attacked with infantry, but were repelled. They returned with artillery fire, and then a cavalry charge. The entire battle took eight hours. At the end, there were 2,000 Paraguayan dead versus 46 dead among the allied forces. The date of the battle, August 16, is now recognised as a Paraguayan national holiday (Children's Day) to remember the sacrifice of those children involved.

The Paraguayan War had a significant impact on the development of all South American nations involved. The region's disputed borders were clarified once and for all … in Brazil and Argentina's favour. Most of the territory in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso do Sul, south of Bonito, was officially incorporated as a result of this agreement. Aside from the devastation of Paraguay, the death toll among the allied forces was also high due to the intensity of the Paraguayan resistance, the difficult terrain and remoteness of locations where battles were fought, and logistical inexperience of the commanders running the campaign. The expenditure required by the victors to win the war also generated large debts to European powers, such as Britain, which required decades to pay off. It's also been suggested that the war hastened the end of Brazil as an Empire and the abolition of slavery. It's also credited with helping unify the confederated states of Argentina into a single nation state.

Notably, Paraguay became involved in a second major conflict, the Chaco War with Bolivia in 1932-35. The prize was the arid Chaco scrubland west of the Pantanal which was then suspected to contain vast oil deposits. Despite having the weaker army (on paper) the tenacity of the Paraguayan soldiers, and their familiarity with their environment led them to victory over the larger and better equipped Bolivians. Areas within the Paraguayan and Bolivian Pantanal were strategically important due to their proximity to the Paraguay river, and river transport. Bahia Negra was used as a base for a Paraguayan flying boat squadron. Puerto Suarez (and nearby lakes) were a base for Bolivia's river navy. The presence of Bolivian aircraft bombing and strafing ships in the Paraguay river resulted in the Brazilian navy having to form armed convoys to safely escort cargo and passenger vessels headed to and from Corumbá.

Image credits: Painting of Battle of Riachuelo, by Victor Meirelles.

Photos: Bandeirante, Sunset, and Kingfisher (Andrew Mercer)

Pantanal Escapes