Corumbá

History

Corumbá was founded on 21 September 1778 under orders of the Mato Grosso territory governor by Sergeant-Major Marcelino Rois Camponês. It was intended as a strategic post protecting the Portuguese colony's frontier from raids by Indian tribes and the neighbouring Spanish Empire - safeguarding supply routes for the remote region, and the return shipments of gold mined in areas further north. The town's original name was Vila Nossa Senhora da Conceição de Albuquerque, before changing to Albuquerque Novo, then Santa Cruz de Corumbá ... and then finally just Corumbá. Ironically, the site of the original settlement is now occupied by neighbouring Ladário.

The Paraguayan War

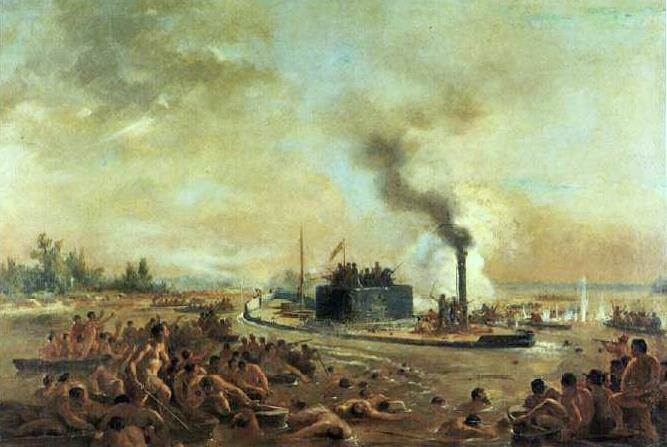

Corumbá's initial growth was slow. Although the growth of steamship traffic and commerce along the Paraguay river made Corumbá an important riverport, the town itself was still no bigger than a village until the mid 19th century. However, in December 1864, the town and region provided the backdrop for the opening shots of Latin America's bloodiest war when neighbouring Paraguay mounted an invasion of Brazil's Mato Grosso territory.

The first battle occurred on 27 December 1864 at Forte Coimbra situated along the river south of the town - with the main Paraguayan invasion force arriving in Corumbá several days later. Brazilian soldiers fleeing Forte Coimbra had initially passed through the town, bringing word of the invasion. A committee was convened to discuss the defence of the town, but decided to abandon. However, rather than organise an orderly evacuation the committee, itself, fled on a ship along with the soldiers - leaving other residents to take their chances fleeing into the Pantanal. The Paraguayan invaders were poorly armed with outdated weapons and weren’t well-led. The expedition’s leader, Colonel Vincente Bairros (appointed because he was the Paraguayan President’s brother-in-law) was reportedly so drunk during his initial assault on Fort Coimbra that it rendered his orders unintelligible. The Paraguayan victory was made possible only through the bravery of his foot-soldiers and the eagerness of the Brazilians to abandon their positions. The shock of the unexpected invasion, and the ensuing panic, caused Brazilian soldiers to abandon defensible positions - leaving weapons and huge stockpiles of ammunition which lasted the Paraguayans for years.

On reaching the town and discovering it empty, Barrios sent his soldiers out, dragging the residents back into town. They returned to discover that the town had been completely ransacked, right down to the door hinges, wallpaper and anything else which caught the impoverished Paraguayan soldiers' eye. Everything was packed onto steamships and sent downriver to the Paraguayan capital in Asuncion. Women of the town were also abused, including by Barrios himself who took the lead and ordered women taken to him onboard his steamer. Many Brazilians and other foreign nationals within the town were taken to Asuncion for use as forced labour - with anyone who interfered being beaten, shot or lanced.

The town remained occupied for over two years, despite nearby battles and skirmishes as a small number of remaining Brazilian soldiers fought back using guerrilla tactics. The town was briefly re-taken on 13 June 1867, when a newly strengthened Brazilian force came downriver from Cuiabá led by Lt. Col. Antonio Maria Coelho - with a pitched battle being fought in the area now occupied by the Praça da República. Despite the victory, there was little to celebrate as the town had been stripped and burned by the fleeing Paraguayans. A smallpox epidemic caused the Brazilians to abandon the town again in late-July, unwittingly taking the epidemic back to Cuiabá where it killed half of that town's 10,000 inhabitants. The Paraguayans re-entered and remained until April 1868 when Brazilian gains at Humaitá caused Paraguay's president Solano López to recall his troops.

Forte Junqueira is one of five historic gun emplacements constructed at the end of the Paraguayan War in 1871 to defend the Corumbá river port.

The Post-War Boom

After the war, Corumbá needed to be rebuilt from scratch. This was a slow process, but was helped by the town quickly regaining its position as a major river port. It was also helped by an economic boost that came with the increased food production and market needed to provide for large military garrisons and the river navy now stationed there. The rebuilt town was laid out with wide streets and modern comforts.

By the end of the 19th Century, Corumbá was Latin America's third largest river port. It exported animal skins (jacaré, jaguar, and otter), dried beef, fish, yerba maté, medicinal plants and handled freight for valuable rubber being shipped down from the Bolivian Amazon and Guaporé regions. Corumbá was transformed into the "emporium of Mato Grosso" hosting foreign traders, consulates, and 25 international banks - with town's primary currency being Pounds Sterling. Reknowed British explorer, Col. Percy Fawcett, based himself in the town while planning expeditions in the early 1920s - praising Corumbá's development, modernity and culture. Another explorer was Former US President Theodore Roosevelt, travelling with Cândido Rondon and using the town as a base to test equipment and prepare for their exploration of the "River of Doubt" in the Brazilian Amazon in 1913-14.

Corumbá's demographics differed from the other Pantanal settlements, drawing immigrants from Europe, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey, and other South American countries. One visiting army officer in 1913 remarked: "At the hotel, the bar, the trading houses, and everywhere in this small and distant Babel, one hears all languages. I wouldn't be exaggerating to say that Portuguese isn't the most spoken language"

The completion of a railroad extension to the town in 1914 led to significant change over the next few decades. Rather than being shipped downriver towards Buenos Aires, exports started being shipped by rail directly to São Paulo. Gradually the focus shifted from the river port towards other railway centres such as Campo Grande. The trading houses closed or moved away - leaving the town to fall into decline.

Curse of Frei Mariano

The town's decline is often cited as resulting from a curse made by Frei (Brother) Mariano. Frei Mariano de Bagnaia was an Italian priest based in the town, who considered himself a hero of the Paraguayan War. His curse arises from the construction of the Nossa Senhora da Candelária Church, which overlooks the Praça da República square. One version of the story says that he asked the Bishop for the church to be dedicated in his honour, but was refused. Another version says that Frei Mariano ordered a clock for the bell tower from an Italian clock maker after a local politician promised to pay - only to have the politician renege on his promise. The clock maker accused the priest of being a deadbeat, which was then made worse by the politician (who owned the local newspaper) repeating the accusation and convincing the local populace to boycott his masses.

When the angered priest was leaving after being recalled to São Paulo, he shook the dust from his sandals before entering the carriage, loudly proclaiming:

This city, and not even its dust, will ever rise.

Legend has it that the priest buried his sandals in a secret location, and that the city's prosperity would only grow again if they were found. Rua Frei Mariano, one of the town's main streets, was supposedly named in honour of the priest to help break this curse.

Trem da Morte and Smuggling Trade

Many travellers gleefully post about their journey on the dramatically-named Trem da Morte (Death Train) which travels between nearby Puerto Quijarro and the Bolivian city of Santa Cruz. Despite its name, the passage is generally comfortable and relaxed - albeit slow, taking 14-19 hours depending on which train you choose.

There are several stories behind the name's origins. One believed origin is the death of workers who died of Yellow Fever and other illnesses as construction passed through swamps and marshlands. Another story is that the train was also used to transport sick malaria and yellow fever sufferers, and transport lepers. The fact that the railroad was poorly maintained and suffered several derailments in its early years also helped reinforce its bad reputation. Others say that the name originated are poor Bolivians without tickets would stow away, and sometimes fall to their deaths from the train.

These days, malaria deaths, yellow fever deaths, leprosy and derailments are a rarity. However, the rise of the cocaine smuggling trade through the 1970s and 80s led to new versions of the tale. Cocaine smuggling still occurs, but on a much scale as random checks carried out by Brazilian Federal Police of travellers from Bolivia make the route less effective. These days drug smuggling operations typically use private planes and helicopters flown into remote cattle ranches, often cloning the IDs or registrations of other aircraft. Seizures of aircraft and vehicles are frequently reported in the Brazilian press but it's a side of things that (hopefully) tourists will never see.

Most smuggling operations in the region commonly are more mundane, involving shipments of computers, electronic goods, perfumes, cheap subsidised gasoline, pirate DVDs and clothing in from Bolivia and Paraguay - bypassing the very considerable duties which Brazil imposes on these imports. There's also a significant traffic in Brazilian stolen cars going the other way (ably assisted by the Brazilian Police if rumours are to be believed). Access to cheap imported goods is one reason that makes Corumbá a popular option for Brazilian tourists - with a large modern shopping mall stocking a large range of consumer goods just over the Bolivian border in Puerto Suarez.

Select from the options below to learn more about Corumbá.